In the realm of precision measurement and distance detection, two critical technologies stand out: the laser displacement sensor and the rangefinder sensor. While often mentioned together due to their shared use of laser technology, they serve distinct purposes and operate on different principles. Understanding their functionalities, differences, and optimal applications is essential for engineers, technicians, and professionals across various industries.

A laser displacement sensor is primarily designed for high-precision, non-contact measurement of an object's position, thickness, or vibration. It operates on the principle of triangulation or time-of-flight, depending on the model. In the common triangulation method, a laser diode projects a focused beam onto the target surface. The reflected light is then captured by a receiving lens at a specific angle and focused onto a position-sensitive detector, such as a CCD or PSD. The displacement of the light spot on the detector is directly proportional to the distance to the target. This allows for micron-level accuracy in measuring dimensions, detecting warpage, or monitoring real-time displacement in dynamic systems. Common industrial applications include quality control on assembly lines for thickness verification of materials like metal sheets, glass, or rubber, precision alignment in semiconductor manufacturing, and vibration analysis in mechanical engineering.

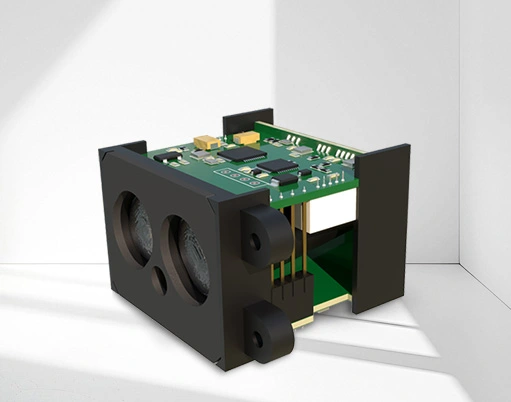

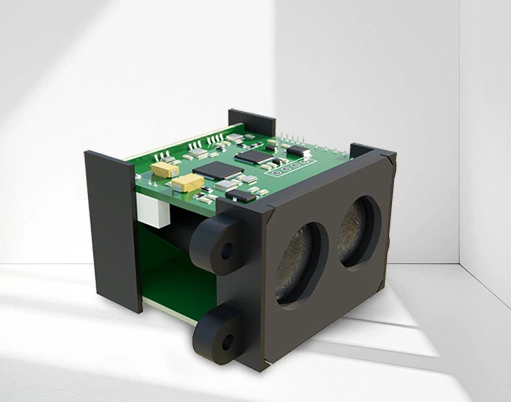

On the other hand, a laser rangefinder sensor is engineered to measure the distance between the sensor and a target over much longer ranges. Its core principle is almost exclusively based on the time-of-flight method. The sensor emits a short pulse of laser light towards the target and precisely measures the time it takes for the reflection to return. Since the speed of light is a known constant, the distance can be calculated with the formula: Distance = (Speed of Light × Time of Flight) / 2. Some advanced models use phase-shift analysis of modulated laser beams for even higher accuracy at shorter to medium ranges. Rangefinders are indispensable in fields requiring long-distance measurement, such as topography and surveying, forestry management, construction site planning, and military targeting. They are also integrated into modern consumer electronics, like smartphones with augmented reality features and advanced camera autofocus systems.

The key distinction lies in their primary design goal: displacement sensors prioritize extreme accuracy at close ranges for relative position changes, while rangefinders prioritize measuring absolute distance over extended ranges, often with slightly lower precision relative to their scale. For instance, a displacement sensor might measure a 0.01mm change in a part's position from a 100mm reference, whereas a rangefinder might measure the 150-meter distance to a building with a centimeter-level accuracy.

Choosing between the two depends entirely on the application's requirements. When the task involves monitoring minute variations, profiling surface contours, or ensuring tight tolerances in manufacturing, a laser displacement sensor is the unequivocal choice. Its high sampling speed and resolution make it ideal for automated inspection systems. Conversely, for applications like mapping, navigation, long-range obstacle detection for autonomous vehicles, or measuring large structural dimensions, a laser rangefinder sensor is the appropriate tool.

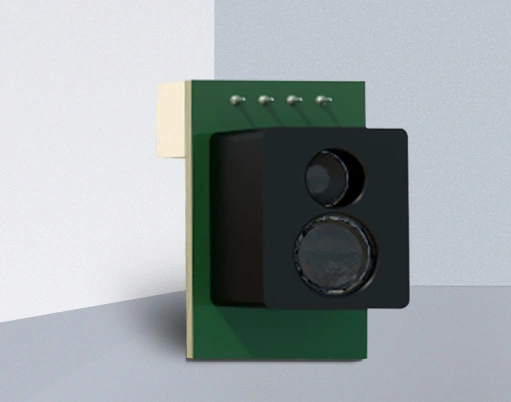

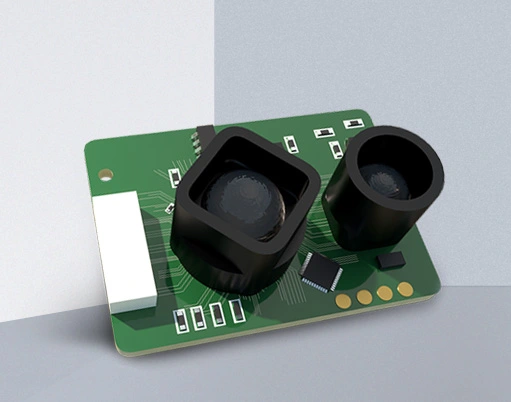

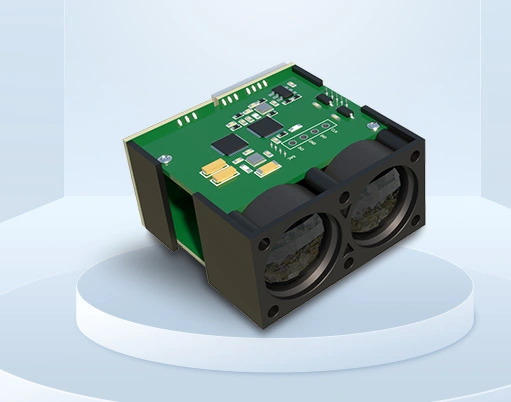

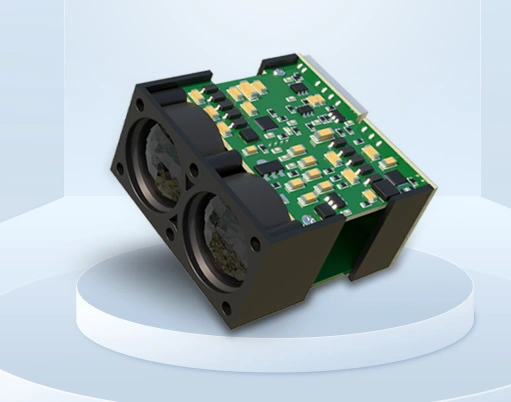

Recent advancements are blurring some traditional boundaries. Some modern sensors combine both functionalities, offering configurable modes for high-precision displacement measurement and extended distance ranging. Furthermore, improvements in laser diode efficiency, detector sensitivity, and signal processing algorithms continue to enhance the performance, reduce the size, and lower the cost of both sensor types.

In conclusion, both laser displacement sensors and laser rangefinder sensors are pillars of modern metrology and sensing technology. By leveraging the properties of coherent light, they provide solutions that are faster, more accurate, and less intrusive than mechanical measurement methods. A clear understanding of their operational principles and intended use cases enables professionals to select the right tool, thereby optimizing processes, ensuring quality, and driving innovation in fields ranging from advanced manufacturing and robotics to geospatial sciences and beyond. Their continued evolution promises even greater integration into the intelligent systems of the future.