Distance transducers represent a critical category of sensors in modern industrial automation, measurement, and control systems. These devices convert a physical displacement or distance into a standardized electrical signal, enabling precise, non-contact, or contact-based measurement of position, thickness, vibration, and other geometric parameters. The core function of a distance transducer is to provide reliable, accurate, and real-time data about the spatial relationship between the sensor itself and a target object. This data is fundamental for process control, quality assurance, robotic guidance, and predictive maintenance across countless industries.

The operational principles of distance transducers vary significantly, leading to distinct types suited for different environments and requirements. One of the most common technologies is the inductive transducer. It operates by generating an electromagnetic field from a coil. When a conductive metallic target enters this field, eddy currents are induced, which alter the coil's impedance. This change is linearly proportional to the distance between the sensor and the target. Inductive sensors are robust, resistant to dirt, oil, and moisture, and excel in harsh industrial settings, but they are limited to detecting metallic objects.

In contrast, capacitive transducers measure distance by detecting changes in capacitance between the sensor's active surface and the target, which acts as the second plate of a capacitor. This technology can detect both metallic and non-metallic materials (plastics, glass, liquids, etc.), making it highly versatile. However, capacitive sensors are sensitive to environmental factors like humidity and temperature, requiring careful installation and calibration. Another widely adopted non-contact method is based on ultrasonic sound waves. An ultrasonic transducer emits high-frequency sound pulses and measures the time delay of the reflected echo. The time-of-flight is directly related to the distance. These sensors are excellent for measuring longer ranges, detecting transparent objects, and functioning in dusty or foggy conditions, though they can be slower and affected by temperature gradients and air turbulence.

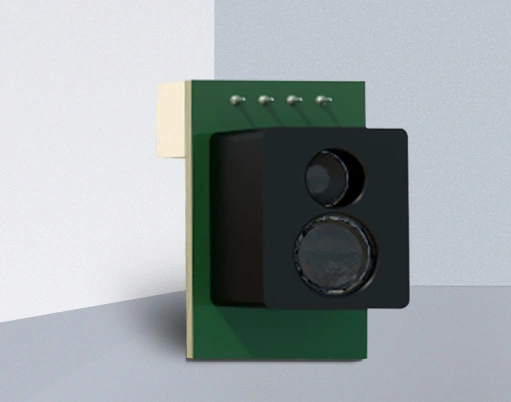

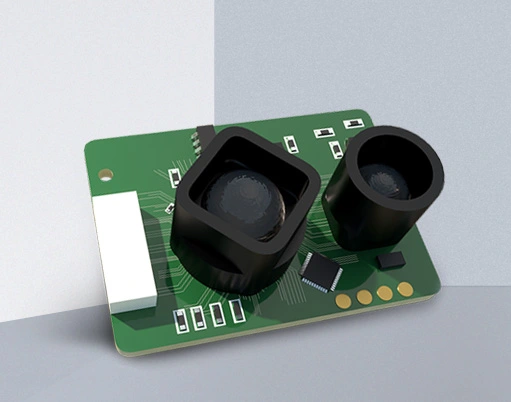

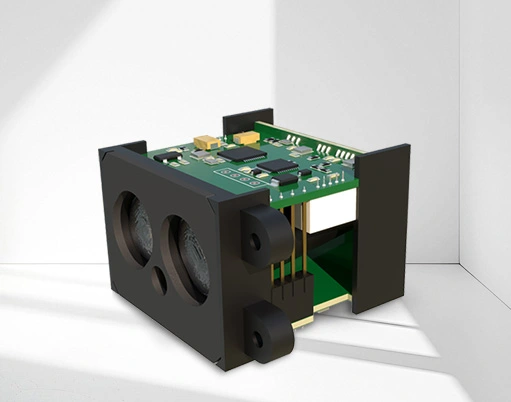

For applications demanding extremely high precision and resolution, laser-based or optical triangulation sensors are often the preferred choice. They project a focused laser beam onto the target, and a receiving lens captures the reflected spot's position on a light-sensitive array (like a CCD or PSD). The spot's position shifts as the target distance changes, allowing for micron-level accuracy. Eddy current sensors, a subtype of inductive sensors, offer high resolution and frequency response for precise displacement measurement of conductive materials, often used in vibration monitoring of rotating machinery.

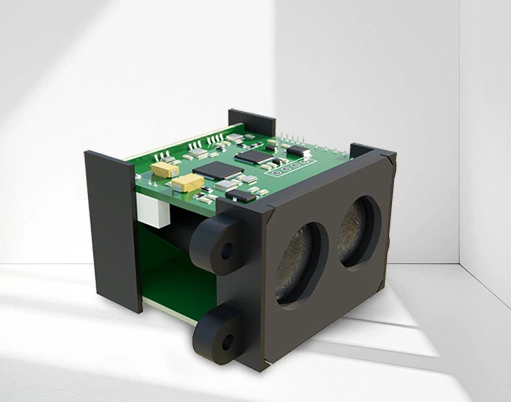

The selection of an appropriate distance transducer is a systematic process that must align with the specific application's demands. Key parameters to consider include measuring range, resolution, accuracy, linearity, and response time. The nature of the target material (metal, plastic, liquid, color) is paramount, as it dictates whether inductive, capacitive, or optical principles are viable. The operating environment presents another critical filter; factors such as temperature extremes, presence of contaminants (dust, oil, coolant), explosive atmospheres (requiring intrinsically safe designs), and mechanical shock/vibration will determine the required sensor housing, ingress protection (IP) rating, and construction robustness.

Output signal type is also a major decision point. Analog outputs (4-20 mA or 0-10 V) provide a continuous signal proportional to distance, ideal for process control systems. Digital outputs (like IO-Link, RS-485, or Ethernet-based protocols) offer advanced diagnostics, parameterization, and integration into Industry 4.0 and Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) architectures. The mounting conditions, available space, and required stand-off distance (the distance from the sensor face to the middle of its measuring range) must be factored into the mechanical design.

In practical application, distance transducers are the unsung heroes of manufacturing. On assembly lines, they verify part presence, count objects, and control robotic arm trajectories. In metalworking, they measure the thickness of rolled steel or the runout of a rotating shaft. In the automotive sector, they ensure precise gap and flushness between body panels. In packaging, they control fill levels in bottles and the thickness of film or paper webs. Beyond traditional industry, they are integral to aerospace testing, medical device manufacturing, and even consumer electronics assembly.

Maintaining optimal performance involves regular calibration against known standards, ensuring a clean sensing face free of debris, and protecting cables from damage. Understanding environmental compensations, especially for technologies sensitive to temperature, is crucial for long-term accuracy. As technology advances, modern distance transducers are becoming smarter, smaller, and more integrated, with built-in microprocessors for linearization, temperature compensation, and self-diagnostic functions. The convergence of precise sensing with digital communication is paving the way for more adaptive, efficient, and interconnected automated systems, solidifying the distance transducer's role as a foundational component in the intelligent factory of the future.