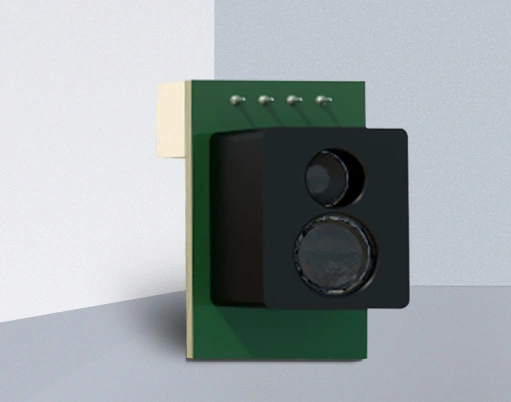

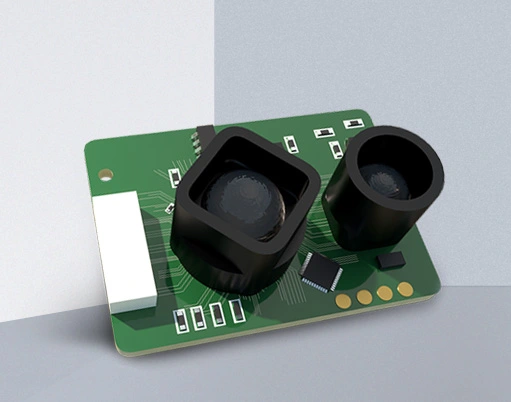

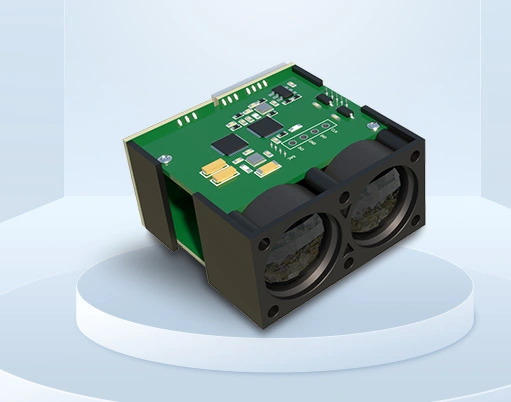

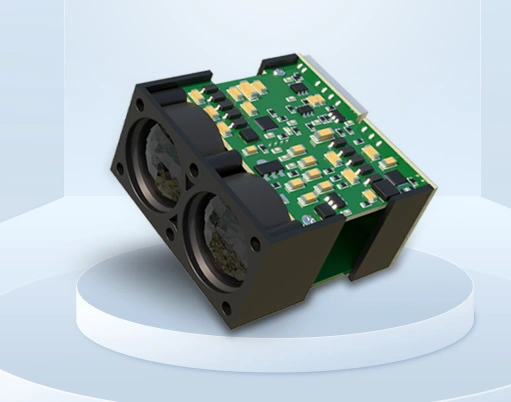

Transmissive optical sensors represent a fundamental category of photoelectric devices widely utilized across industrial automation, consumer electronics, and scientific instrumentation. These sensors operate on a straightforward yet highly effective principle: they consist of an aligned emitter and receiver pair, typically an infrared LED and a phototransistor or photodiode, separated by a gap. The emitter continuously projects a beam of light toward the receiver. When an object passes through this gap, it interrupts the light beam, causing a detectable change in the receiver's output signal. This binary state change—from light received to light blocked—enables precise detection of object presence, position, counting, or speed without physical contact.

The core advantage of transmissive sensors lies in their reliability and simplicity. Since the light path is direct and confined, they are less susceptible to ambient light interference compared to some reflective sensor types, offering stable performance in varied environments. Their design allows for high-speed detection, capable of sensing objects moving at rapid velocities, which is critical in manufacturing lines for inspecting small components like semiconductor chips, pills, or fast-moving packaging materials. The output is typically a clean digital signal, easily interfaced with microcontrollers, PLCs, or other logic circuits for immediate processing.

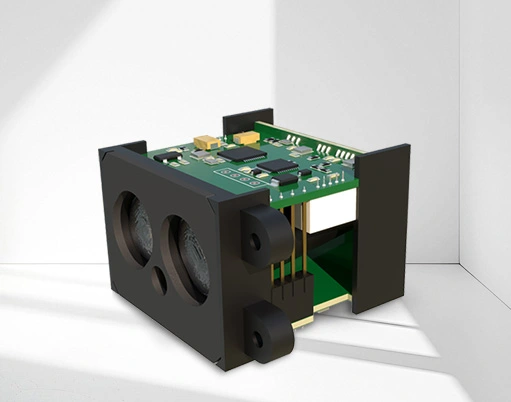

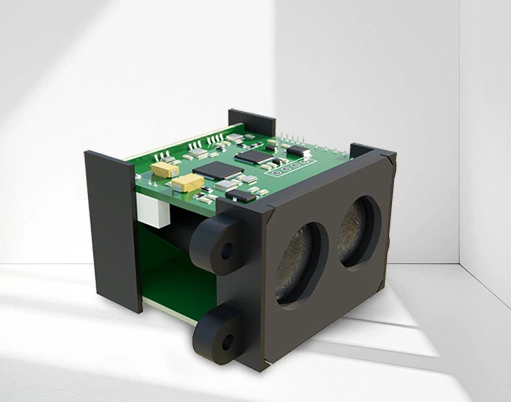

Key performance parameters for selecting a transmissive optical sensor include sensing distance, response time, light source wavelength, and environmental durability. Sensing distance, or the gap length between emitter and receiver, can range from a few millimeters to several meters, depending on the light intensity and lens design. For long-range applications, focused lenses or laser diodes may be employed to maintain a collimated beam. Response time, often in the microsecond range, determines how quickly the sensor can detect an interruption, directly impacting system throughput. Infrared wavelengths around 880-950 nm are common as they minimize interference from visible light while offering good component availability. For harsh industrial settings, sensors are housed in rugged enclosures with ingress protection ratings to withstand dust, moisture, and mechanical vibration.

Applications of transmissive optical sensors are extensive. In industrial automation, they are ubiquitous on assembly lines for object detection, part counting, and limit switching. They form the essential mechanism in rotary encoders, where a slotted disk interrupts the beam to measure rotation speed or position. In consumer printers, these sensors detect paper presence and track paper movement by sensing interruptions from perforated encoder strips or wheels. Security systems employ them in intrusion detection beams across doorways or perimeters. Additionally, they are found in vending machines to verify product dispensing, in medical devices for fluid level sensing, and in scientific instruments for precise alignment or particle detection.

When integrating a transmissive sensor, proper alignment of the emitter and receiver is paramount; even slight misalignment can drastically reduce signal strength. Designers must consider the object's characteristics—opaque objects reliably block light, while transparent or translucent materials may require sensors with adjusted sensitivity or specific wavelengths. Regular maintenance, such as cleaning the lenses to prevent dust accumulation, ensures long-term accuracy. Modern advancements include miniaturized surface-mount versions for compact electronics, smart sensors with integrated amplification and diagnostics, and models with modulated light signals to further enhance immunity to ambient optical noise.

In summary, the transmissive optical sensor remains a cornerstone of non-contact sensing technology due to its direct operational principle, robustness, and versatility. Its ability to provide fast, reliable binary detection makes it an indispensable component in countless systems where precise, wear-free sensing of object presence or motion is required. As technology evolves, these sensors continue to adapt, offering greater precision, smaller form factors, and enhanced connectivity for the increasingly automated world.